Doctors and drug developers were stunned when they first saw imaging results from an innovative form of targeted radiotherapy. In a clinical trial, a treatment developed by Novartis succeeded in completely eliminating widespread cancer in some patients within just six months.

Dr. Michael Morris, an oncologist at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, described the results as “astonishing” and “unprecedented,” with tests showing that about 9% of participants were completely cancer-free in the first trial, increasing to 21% in the second trial.

Although Novartis has been developing cancer drugs for decades, it has become a pioneer in radioligand therapy after acquiring the technology through two deals: the first in 2017 by purchasing Advanced Accelerator Applications, founded by scientists from CERN, and the second in 2018 with a $2.1 billion acquisition of the American biotech company Endocyte.

Traditional radiotherapy treats about half of cancer patients by directing radiation from outside the body to target cancer cells, but it often damages surrounding healthy tissue. Radioligand therapy, however, is administered intravenously as a solution containing radioactive isotopes linked to ligands—molecules that bind to specific receptors on cancer cell surfaces—allowing a precise and concentrated radiation dose to the tumor while minimizing damage to healthy tissue.

The drug Lutathera, acquired by Novartis through the Advanced Accelerator deal, was the first approved treatment in this category, receiving initial approval in 2017 for certain gastrointestinal cancers. In 2022, the company obtained the first U.S. approval for Pluvicto to treat prostate cancer, later expanding its use to patients in earlier disease stages.

In estimating the potential market size, Novartis CEO Vasant Narasimhan predicted in 2021 it would reach about $10 billion, but earlier this year he told the Financial Times that the market could range between $25 and $30 billion if expectations are met.

However, this promising treatment faces huge logistical challenges, requiring production of radioactive isotopes in nuclear reactors, followed by manufacturing, transporting, and delivering the radiopharmaceuticals to patients under strict safety standards—obstacles Novartis has worked for years to overcome.

Other pharmaceutical companies have started to see promising opportunities in this field and are racing to innovate. In 2023 and 2024, Eli Lilly (USA), AstraZeneca (UK), and Sanofi (France) acquired startups developing radioligand-based therapies.

Philip Holtzer, CEO of Radioligand Chemistry at Novartis, said startups in this field are emerging “like mushrooms,” as are suppliers of radioactive isotopes. He added, “A large market is currently forming.”

Novartis is currently conducting 15 clinical trials involving 7 potential radioligand therapies, along with several preclinical projects. The company is expanding research to explore diverse isotopes, develop combination therapies, and extend therapeutic applications to additional cancers including lung, breast, pancreatic, and colon cancers.

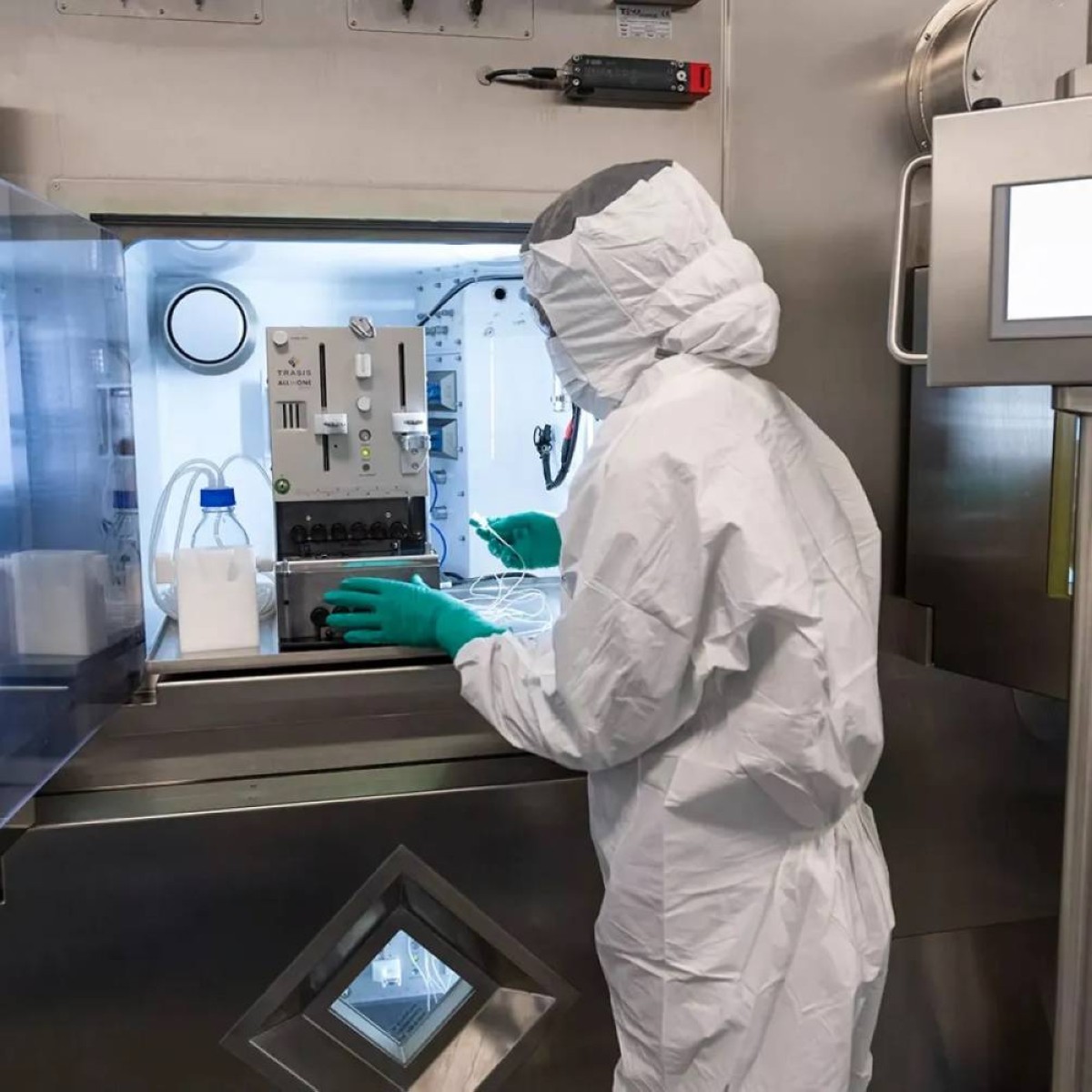

At Novartis’ headquarters in Basel, Switzerland, the main radioligand therapy lab underwent special structural modifications, reinforced to accommodate 40 tons of lead to prevent radiation leakage. All scientists working in the lab wear two radiation dose monitors—one miniaturized on the finger—to precisely track their radiation exposure.

Researchers are working to broaden the effectiveness of this therapy to cover a wider spectrum of cancers. Vasant Narasimhan said, “Each cancer type will have a unique solution,” adding, “Nothing in the human body can be handled with a plug-and-play approach; you have to face and solve different challenges.”

Once new radioligand therapies receive official approvals, another challenge arises: mass commercial production. Novartis has already secured a large share of lutetium-177 isotope supplies, prompting competitors to seek alternatives such as actinium isotopes. Since Russia is a major source of actinium, companies are looking to secure alternative sources elsewhere.

After producing the radioactive material, the company has only three to five days to manufacture the drug and deliver it to the patient before radioactive decay reduces its effectiveness. Each vial is custom-made for a specific patient according to their treatment schedule. Novartis previously faced difficulties meeting demand for Pluvicto, but now reports that 99.5% of doses are delivered on the planned day.

Stephen Lang, Head of Operations at Novartis, explained that the radioactive isotope must bind precisely to the molecule targeting cancer cells and then undergo quality tests. He added, “It’s not just about speed; the dose must be correct on the first try.”

A specialized team works around the clock to track vials equipped with GPS systems, while Novartis has begun employing generative AI to predict logistical issues and select optimal routes to hospitals. To reduce distances between manufacturing sites, hospitals, and patients, the company is expanding its manufacturing network—currently limited to six plants in the US and Europe—by adding new facilities in China, Japan, and additional US regions.

Additional challenges arise when administering radioligand therapy to patients; unlike external radiotherapy, the radioactive material remains inside the patient’s body and continues to be active after dosing. Some countries, such as Germany and Japan, require patients to stay isolated overnight in shielded hospital rooms to prevent radiation leakage, but very few companies can currently build such specialized facilities. Doctors also need special training to handle these patients. In some countries, patients’ urine must be collected and stored for 70 days until the radioactive activity decays.

Carla Panziger, Portfolio Manager at asset management firm Fontopel, a Novartis investor, believes that despite these obstacles, targeted therapies of this kind represent the “future of cancer treatment.” She added that 2025 will be a milestone year for Novartis, especially after expanded approval of Pluvicto, which doubled the potential patient population. However, Panziger expects building the integrated system needed to adopt radioligand therapy as a main treatment option will take 10 to 15 years.

Recommended for you

Exhibition City Completes About 80% of Preparations for the Damascus International Fair Launch

Talib Al-Rifai Chronicles Kuwaiti Art Heritage in "Doukhi.. Tasaseem Al-Saba"

Unified Admission Applications Start Tuesday with 640 Students to be Accepted in Medicine

Egypt Post: We Have Over 10 Million Customers in Savings Accounts and Offer Daily, Monthly, and Annual Returns

Al-Jaghbeer: The Industrial Sector Leads Economic Growth

Women’s Associations Accuse 'Entities' of Fueling Hatred and Distorting the Image of Moroccan Women