Kuala Lumpur – On the 68th anniversary of their independence, Malaysians recall the historic moment when the last colonial flag, “the flag with intersecting crosses in red, blue, and white,” was lowered, and the independence flag was raised as a symbol of freedom and sovereignty.

This flag, featuring a crescent, a shining sun, and red and white stripes representing the number of states forming the new Malaysia, was initially 11 states, with 3 more joining six years later.

Over these decades, Malaysia has reduced poverty to 6% by 2025, down from over 50% immediately after independence on August 31, 1957.

World Bank expert Borva Sangi told the Malaysian news agency Bernama that his country has progressed beyond many nations that shared its independence journey, such as neighboring the Philippines and Zambia in Africa, noting Malaysia now aims to “zero out poverty” following its neighbor Singapore’s example.

This Malaysian history reminds citizens that no matter how long colonialism lasts, its fate is disappearance, and progress can be achieved when popular will and political leadership align.

Centuries before colonialism, the Malacca Sultanate in the 14th century ruled the east coast of the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra Island through the strait bearing its name. Its strategic location on the Malacca Strait provided significant economic and political advantages, linking East Asia and the Middle East.

The Sultanate’s adoption of Islam – by rulers and people – strengthened trade relations with South India and the Arab region, alongside traditional ties with China. The strait, over 800 kilometers long and 50 to 320 kilometers wide, connected the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea.

Notably, descendants of ancient Muslim migrants from India dominate Malaysia’s banking sector today, a profession inherited from ancestors who exchanged goods and currencies aboard ships anchored in the strait. As trade was a gateway to prosperity, Islam was a factor of stability, security, and peace.

The strait remains strategically important today, with about 94,000 ships passing annually, representing over 30% of global trade. With China’s rise as a major economic power over the past three decades, the term “strait dilemma” emerged, as 80% of Beijing’s imports and exports pass through it.

These facts have driven Chinese leadership to seek alternatives via routes in Myanmar and Pakistan, and proposed ones with Thailand to link the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean through the Andaman Sea.

The founding of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) in 1946 was a central step towards liberation, providing Malays with an official framework to negotiate with British colonialists and laying the foundations of an independent state. The Federation of Malaya was declared in 1948, uniting the western peninsula states.

In 1956, the three ethnic groups forming the federation (Malays, Chinese, and Indians) held a meeting where Chinese and Indian leaders recognized Malay political sovereignty represented by the sultans, in exchange for granting citizenship to those then considered “foreigners.”

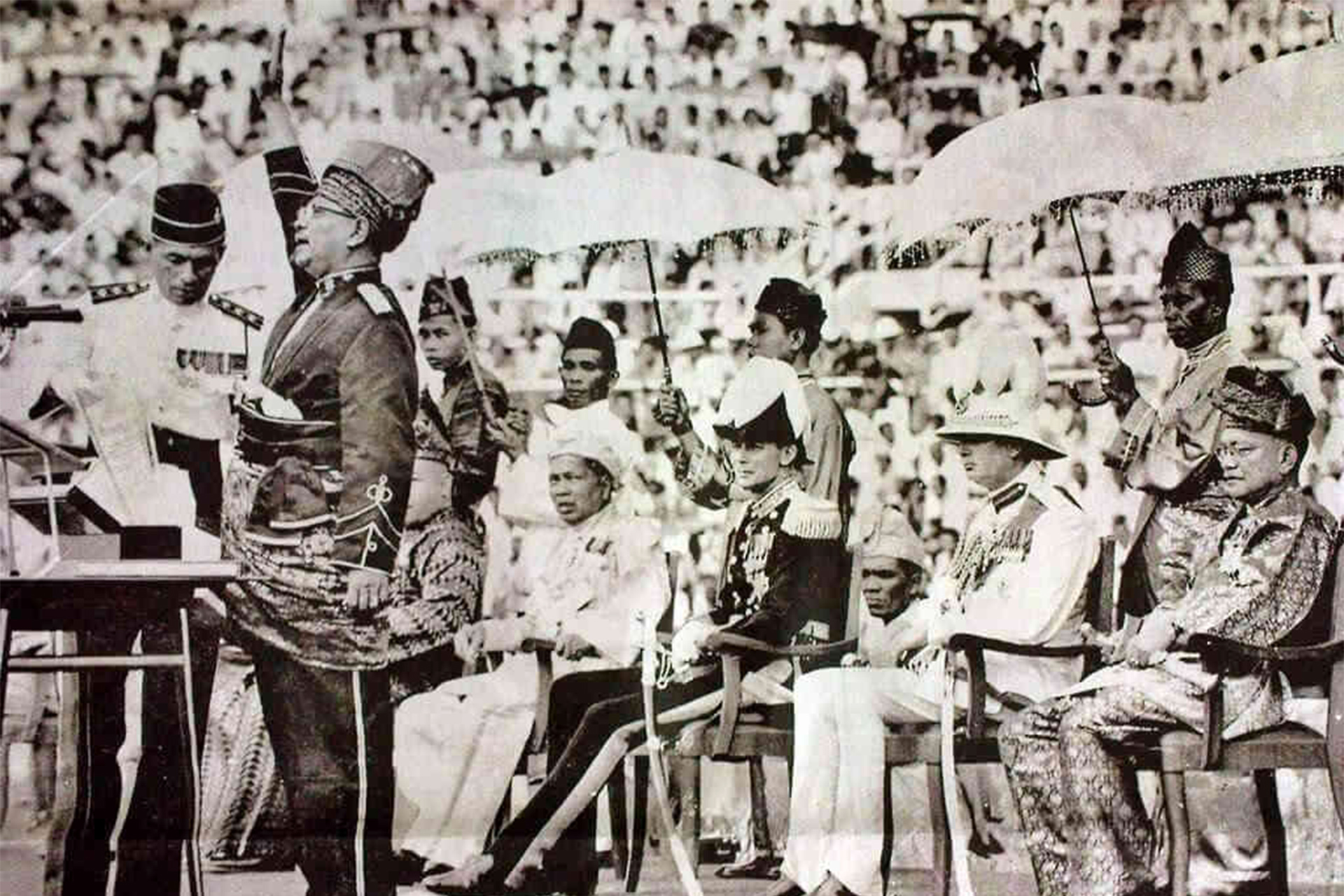

Based on this agreement, Tunku Abdul Rahman and his team led negotiations with Britain that culminated in the independence declaration on August 31, 1957.

Six years later, the states of Sabah, Sarawak, and Singapore joined the new federation, but Singapore later withdrew by mutual agreement ratified by the Malaysian parliament.

The social contract was considered the foundation of independence, dispelling British colonial preconditions that required political and social consensus before granting freedom. However, subsequent years witnessed ethnic violence between Malays and Chinese due to economic grievances felt by the former, leading to the resignation of the first Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman.

Later, his successor Abdul Razak Hussein adopted a new economic policy in 1971 aimed at addressing disparities among ethnic groups by granting indigenous “Bumiputra” priority in education, economy, and administration, in a 20-year plan to bridge the gap with other communities.

European colonization of Malacca began in 1511 when the Portuguese overthrew the local sultan after a naval campaign supported by advanced artillery. In 1614, the Dutch ousted the Portuguese before ceding the country to the British under the 1824 treaty. Unlike their predecessors, the British intervened in internal affairs, sparking a series of revolts.

However, educational and cultural renaissance in the early 20th century helped ignite national spirit, especially with student exchanges with the Arab world and the emergence of local press like “The Sultan’s Message.” World War II, when the Japanese occupied the region, accelerated liberation awareness as the new colonialism sparked widespread rejection before the Japanese defeat and British return in 1945, marking the decisive phase of the struggle.

Historians note that the assassination of British governor Henry Gurney in 1951 was a turning point that pushed London to hasten independence talks, especially as socialist influence supported by China expanded. Britain bargained with the sultans for independence in exchange for their distancing from socialist resistance.

Despite achievements, Malaysia today faces multiple challenges including declining political stability, ongoing corruption, rising inflation amid weak income growth, as well as climate change impacts and rising sea levels.

Maintaining balance in foreign relations remains a key challenge, especially between the US and China amid escalating tensions. The situation is further complicated by regional disputes in the South China Sea, where Beijing insists on treating the sea as its semi-private domain.

Domestically, Singapore’s exit from the Malaysian federation still casts constitutional shadows, as the agreement for the three states’ joining granted them a one-third share in parliament to prevent the Malay Peninsula from unilaterally amending the constitution. With Singapore’s departure, Sarawak and Sabah lost this veto, reducing their parliamentary representation by 15 members to a quarter instead of a third.

Disputes continue over ownership of gas and oil fields, alongside administrative issues in health, education, and delayed projects. There are also demands to preserve the cultural and religious identity of the two states, especially since Muslims constitute only about 25% of Sarawak’s population.

Although the central government approved a 20% share of natural resource revenues for the two states, disagreements over calculation mechanisms persist. Additionally, calls are renewed to guarantee fundamental rights through the constitution, keeping them protected from amendment or change.

Recommended for you

Exhibition City Completes About 80% of Preparations for the Damascus International Fair Launch

Talib Al-Rifai Chronicles Kuwaiti Art Heritage in "Doukhi.. Tasaseem Al-Saba"

Unified Admission Applications Start Tuesday with 640 Students to be Accepted in Medicine

Egypt Post: We Have Over 10 Million Customers in Savings Accounts and Offer Daily, Monthly, and Annual Returns

Al-Jaghbeer: The Industrial Sector Leads Economic Growth

His Highness Sheikh Isa bin Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa Receives the United States Ambassador to the Kingdom of Bahrain