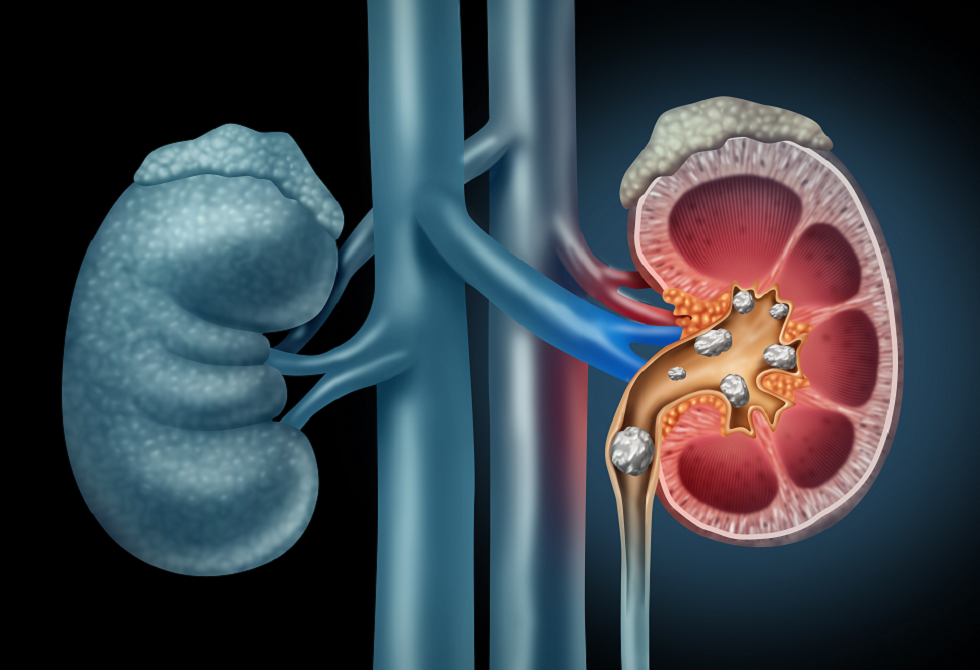

Researchers at Stanford University have developed an innovative technique that could revolutionize the treatment of painful kidney stones by genetically modifying gut bacteria to break down “oxalate,” a major cause of stone formation.

A clinical trial involving 51 volunteers, including 12 with enteric hyperoxaluria—a common cause of recurrent kidney stones—was conducted. Participants were divided into two groups: one received capsules containing genetically modified bacteria, while the other received a placebo. Treatment lasted one month. All participants also consumed dissolved “porphyrin” powder with an antacid to create a suitable environment for bacterial activity. Results showed a significant reduction in oxalate levels in the group receiving the modified bacteria compared to the placebo group.

How the Modified Bacteria Work

The researchers genetically engineered a strain of gut bacteria (Phocaeicola vulgatus) to break down oxalate, a substance found in high amounts in foods like spinach, nuts, dark chocolate, and tea. They also made the bacteria rely on “porphyrin” as a food source—a carbohydrate most gut bacteria cannot digest—allowing the bacteria to survive longer in the gut.

Dr. Weston Whitaker, the study leader, said that relying on porphyrin gives researchers a “kill switch,” enabling them to simply stop the bacteria’s activity by discontinuing the powder intake.

Whitaker believes this method could be used to treat or prevent other intestinal diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease and certain cancers. The team is currently conducting trials on patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

Professor Chris Eden, a consultant urologist, welcomed the study but noted it is still in early stages: “This could be beneficial for a specific group of patients with recurrent kidney stones, especially those who do not respond to a low-oxalate diet.”

Dr. David Riglar, an assistant professor of bioengineering, said, “This is important research, and testing this technology in human clinical trials is critical. There are many unknowns about how gut bacteria interact with our bodies, which poses challenges for microbiome engineering.” He also noted that the study showed the modified bacteria persisted in some participants’ microbiomes even after removing their food source, which requires further investigation.

Recommended for you

Talib Al-Rifai Chronicles Kuwaiti Art Heritage in "Doukhi.. Tasaseem Al-Saba"

Exhibition City Completes About 80% of Preparations for the Damascus International Fair Launch

Unified Admission Applications Start Tuesday with 640 Students to be Accepted in Medicine

Egypt Post: We Have Over 10 Million Customers in Savings Accounts and Offer Daily, Monthly, and Annual Returns

Al-Jaghbeer: The Industrial Sector Leads Economic Growth

His Highness Sheikh Isa bin Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa Receives the United States Ambassador to the Kingdom of Bahrain