There is no point in contesting Al-Burhan’s path following his predecessor Omar Al-Bashir by appointing Mr. Wahbi Mohamed Mukhtar as President of the Constitutional Court. The country lacks a constitution or even a partial one, so neither Wahbi nor anyone else can truly safeguard the rights and freedoms that constitutional courts are meant to protect. This issue goes back to Mr. Jalal Ali Lutfi, the first person appointed by Al-Bashir as head of the Constitutional Court when it was established during his era. Jalal Ali Lutfi was behind undermining the court’s original purpose, which was primarily to protect the constitution by reviewing laws and state decisions that violate it. Instead, Lutfi and his successors turned the Constitutional Court into a third-level court, abandoning constitutional protection and engaging in reviewing Supreme Court rulings on inheritance, criminal, and civil cases.

Constitutional courts are supposed to be the watchdog and safeguard for citizens’ rights and freedoms against decisions and orders issued by the head of state and state officials that contradict the constitution. This is why it is inappropriate and unacceptable for the head of state to appoint the president and members of the Constitutional Court. In such cases, they owe the head of state for granting them such high positions and privileges, knowing their continued tenure depends on the head of state’s satisfaction with their performance according to his wishes. He can dismiss them whenever they invalidate a law or decision issued by him or his followers. (Al-Bashir dismissed the former Constitutional Court president Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah following his participation in an arbitration panel based on a verbal decision conveyed by his deputy Bakri Hassan Saleh).

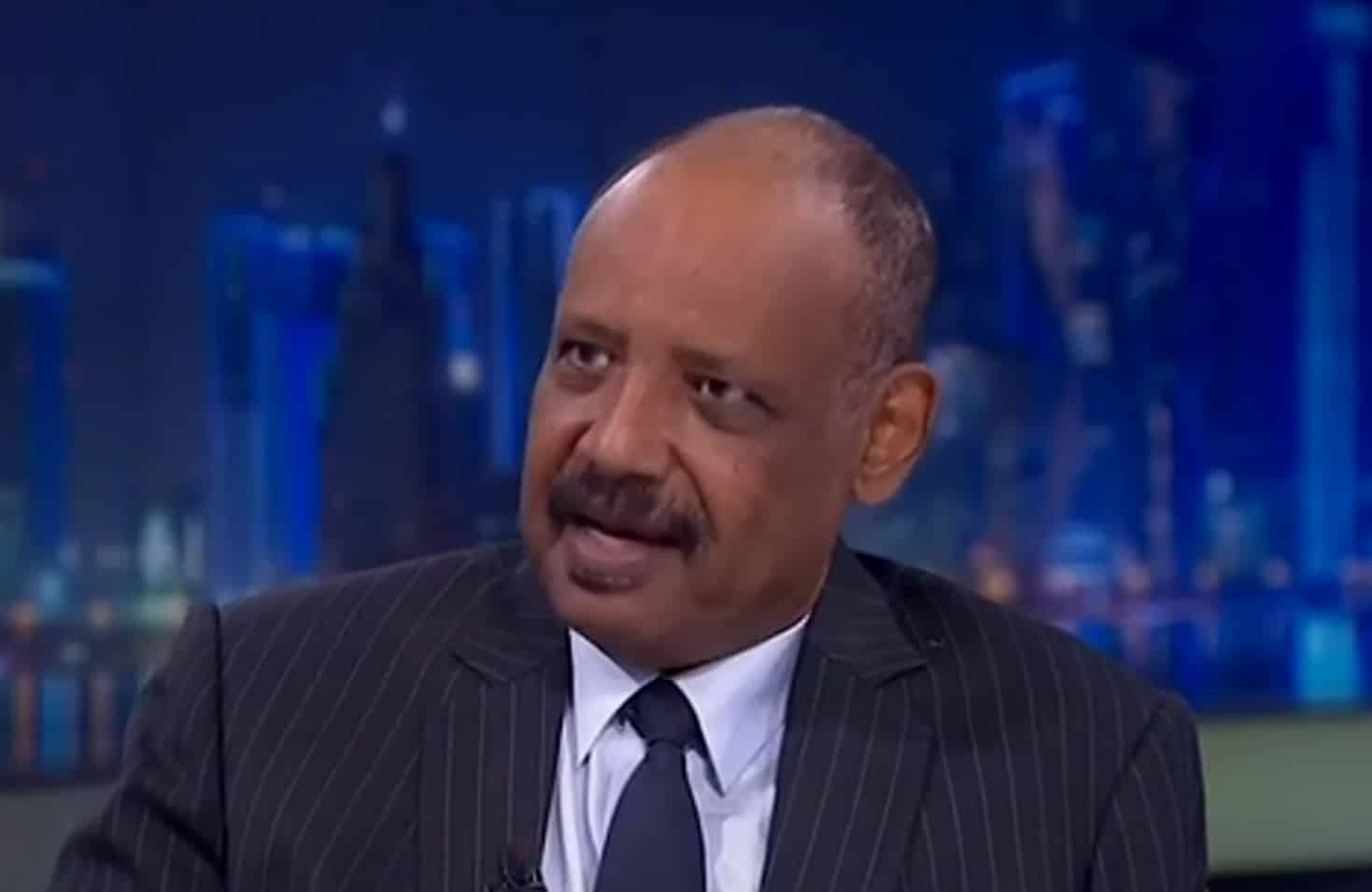

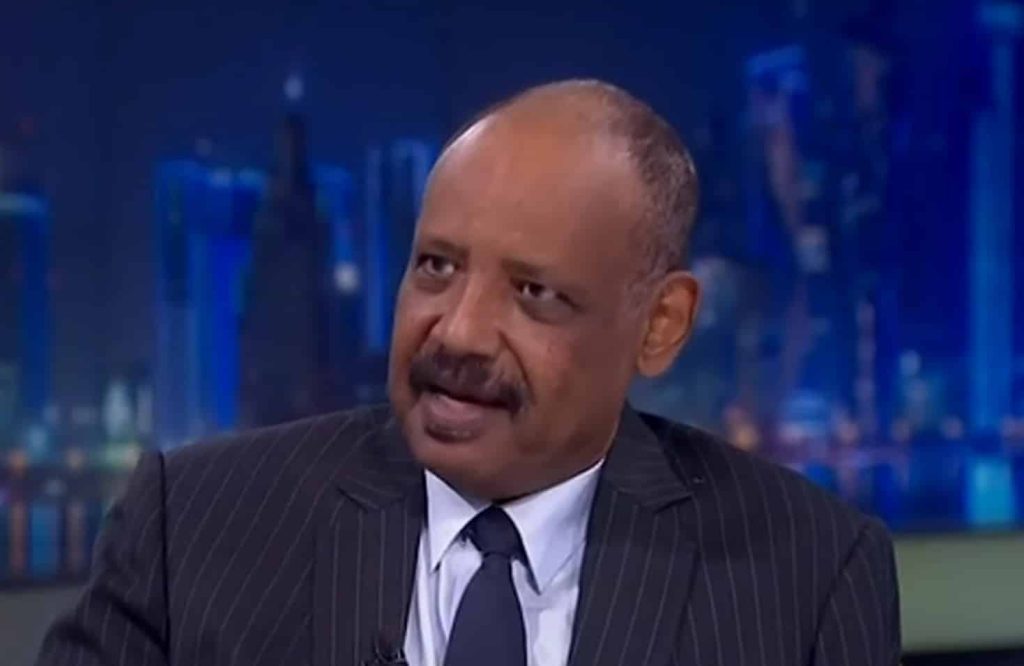

No one can argue that Al-Burhan chose Mr. Wahbi Mohamed Mukhtar to head the Constitutional Court for any reason other than the services he and his predecessor provided to the authoritarian Salvation regime through the court’s rulings and decisions. Here are examples of “principles” established by the Constitutional Court protecting the regime rather than the rights and freedoms enshrined in the constitution:

In the case filed by the newspaper “Masarat” against the Security Apparatus, the Constitutional Court ruled that “prior censorship of publication by security is considered a constitutional authority.” It also ruled in the case brought by Farouk Mohamed Ibrahim against the Security Apparatus that “torture crimes are subject to prescription” and “torture has an Islamic reference.” The court set a precedent in Ammar Najm Al-Din’s case against the Security Apparatus, ruling that “the one-year detention period is considered reasonable.” It ruled in the case of Farouk Abu Issa and Amin Maki Madani against the Security Apparatus that “it is permissible to prevent the detainee from notifying his lawyer.” It also ruled in the case of Wagdy Saleh and others against the Security Apparatus that “dispersing demonstrations and arresting protesters is not unconstitutional.”

Of course, there is no point in discussing the flawed basis on which Al-Burhan relied in appointing Mr. Wahbi Mukhtar as President of the Constitutional Court or what will follow in appointing its members. Al-Burhan today behaves in the country and with its people as an owner does with his property.

Before the Salvation regime, since Sudan’s independence, there was no constitutional court. Constitutional rights were overseen by a division within the Supreme Court, whose judges were commensurate with its size and importance. Among them was the renowned judge Henry Riyad Sakla, a jurist and expert in constitutional law, who contributed an unparalleled legacy to the legal library through the Judicial Rulings Journal studied by successive generations of legal professionals (Judge Henry Riyad was retired for public interest shortly after the Salvation coup and passed away thereafter).

Recommended for you

Talib Al-Rifai Chronicles Kuwaiti Art Heritage in "Doukhi.. Tasaseem Al-Saba"

Exhibition City Completes About 80% of Preparations for the Damascus International Fair Launch

Unified Admission Applications Start Tuesday with 640 Students to be Accepted in Medicine

Egypt Post: We Have Over 10 Million Customers in Savings Accounts and Offer Daily, Monthly, and Annual Returns

His Highness Sheikh Isa bin Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa Receives the United States Ambassador to the Kingdom of Bahrain

Al-Jaghbeer: The Industrial Sector Leads Economic Growth