Hebron is not a passing event but the beginning of a strategic project to divide the West Bank.

Last Friday, Hebrew newspaper reports revealed that the occupying state plans to replace the Palestinian Authority leadership in Hebron with local clans and establish a separate governance that recognizes the occupying state as a “Jewish state” and joins the Abraham Accords for normalization. This is in response to several Western countries’ intentions to recognize the State of Palestine.

Israeli affairs expert Adel Shadid confirms that what is happening in Hebron is not a transient event but the start of a strategic project through which the occupying state seeks to divide the West Bank and transform the Authority from a central entity into a group of scattered local authorities similar to municipalities and village councils.

Shadid says this division, and the fact that part of Hebron city and governorate remains under full Israeli security, administrative, and life control, encouraged Tel Aviv as well as some parties willing to engage with the occupation to revive a similar experience to the “Village Leagues” project tried in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which also started in Hebron but was foiled thanks to the steadfastness of the Palestinian people and their national forces.

Shadid explains that the situation in Hebron completely changed after the Redeployment Agreement in 1997, as the agreement did not remain the same after the Second Intifada, with most of Area A, which was under Palestinian security control, effectively canceled.

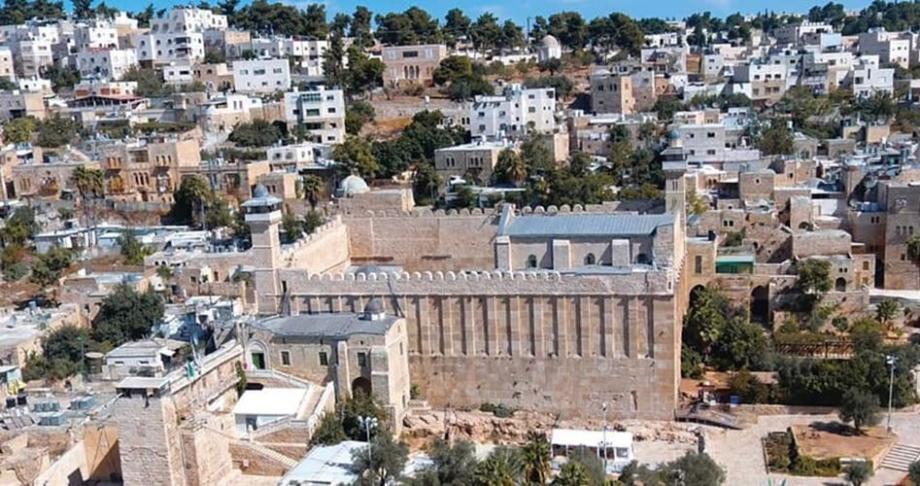

Today, Hebron Governorate, which covers an area of 1100 km² and is home to about 900,000 people, nearly one-third of the West Bank’s population, is fully under Israeli security control.

The occupation army raids, arrests, and demolishes homes day and night, while the Palestinian Authority’s powers are limited to civil and service aspects. Even the movement of PA security apparatus between areas of the governorate requires prior Israeli approval through what is known as “security coordination,” which is often denied.

As in the rest of the West Bank, Hebron is divided into Areas A, B, and C, but with a fundamental difference: all security powers are in the hands of the occupation.

Shadid adds that the most dangerous part of the scene is Area H2, which includes the Old City and the core of Hebron, where the Hebron Agreement left security powers in the hands of the occupying state, while service powers were nominally with the Hebron Municipality. However, even these powers have gradually been withdrawn from the Palestinian municipality by what is called the “settlers’ municipality” in Hebron, meaning reducing its role in favor of the settlers’ authority.

Shadid believes that the absence of security agencies from these areas and the occupation’s refusal to allow them to operate opened the door for the emergence of local figures who do not mind dealing with the occupation.

This recalls the attempt to revive the “Village Leagues” but under different names and forms, by granting some service powers to these groups as part of a larger project to fragment the Palestinian national identity and transform it into local, clan, and regional identities.

Nevertheless, Shadid stresses that this project—despite coinciding with the decline of the Palestinian national movement due to the Oslo Agreement, the ban on Hamas and Islamic Jihad, and Fatah’s transformation into a party subordinate to the Authority—will not succeed.

He recalls the experience of the 1970s and 1980s when the occupying state sought to eliminate the national movement and establish the Village Leagues after the Beirut invasion and the PLO’s exile, but the result was completely opposite, as Palestinians revived their national identity, paving the way for the First Intifada that shocked the world and foiled the Israeli project.

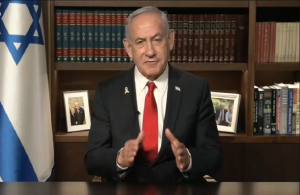

Political analyst and writer Jihad Harb sees Netanyahu’s plan to replace the Authority with clans in the West Bank, specifically in Hebron, as part of a colonial strategy rooted in Talmudic origins aimed at preventing the establishment of an independent Palestinian political entity.

Harb explained that Netanyahu relies on ancient Torah illusions considering the West Bank as “Judaea and Samaria,” an inseparable part of the “Land of the Occupation State.”

He added that since 2022, the occupying state has been intensifying settlement and linking settlements through projects like “E1” to separate the northern West Bank from the south and prevent any possibility of a Palestinian state.

He pointed out that targeting Hebron has religious and political dimensions due to its connection to the Ibrahimi Mosque and its symbolism in Talmudic heritage, yet Palestinian clans refuse to cooperate with the occupation to preserve national constants.

Harb concluded that the occupying state employs financial and military tools to impose its vision, but “the project lacks any genuine Palestinian national response,” and the people stand firmly against it.

On July 6, Hebron clans disavowed in a press conference the proposal to establish a “clan emirate” in the governorate and confirmed their commitment to Palestinian constants.

At that time, Hebron clans’ representative Nafeth Al-Jabari rejected what was included in a report by the American “Wall Street Journal” about a proposal by a member of the Jabari family to “recognize the occupying state as a Jewish state.”

Recommended for you

Talib Al-Rifai Chronicles Kuwaiti Art Heritage in "Doukhi.. Tasaseem Al-Saba"

Exhibition City Completes About 80% of Preparations for the Damascus International Fair Launch

Unified Admission Applications Start Tuesday with 640 Students to be Accepted in Medicine

Egypt Post: We Have Over 10 Million Customers in Savings Accounts and Offer Daily, Monthly, and Annual Returns

His Highness Sheikh Isa bin Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa Receives the United States Ambassador to the Kingdom of Bahrain

Al-Jaghbeer: The Industrial Sector Leads Economic Growth